THE GREAT SHAKA THE ZULU

| Shaka kaSenzangakhona | |

|---|---|

|

|

He is widely credited with uniting many of the Northern Nguni people, specifically the Mtetwa Paramountcy and the Ndwandwe into the Zulu Kingdom, the beginnings of a nation that held sway over the portion of southern Africa between the Phongolo and Mzimkhulu Rivers, and his statesmanship and vigour marked him as one of the greatest Zulu kings. He has been called a military genius for his reforms and innovations, and condemned for the brutality of his reign. Other historians debate about Shaka's role as a uniter, versus a usurper of traditional Zulu ruling prerogatives, and the notion of the Zulu state as a unique construction, divorced from the localised culture and the previous systems built by his predecessor Dingiswayo. Research continues into the character and methods of the Zulu warrior king, whose reign still greatly influences South African culture.

Early life Shaka was the first son of the chieftain Senzangakhona and Nandi, a daughter of Bhebhe, the past chief of the Elangeni tribe, born near present day Melmoth, KwaZulu-Natal Province. He was conceived out of wedlock somewhere between 1781 and 1787.

Shaka spent his childhood in his mother's settlements. He is recorded as having been initiated there and inducted into an ibutho lempi (fighting unit). In his early days, Shaka served as a warrior under the sway of local chieftain Dingiswayo and the Mthethwa, to whom the Zulu were then paying tribute.

Dingiswayo called up the emDlatsheni iNtanga (age-group), of which Shaka was part, and incorporated it in the Izichwe regiment. Shaka served as a Mthethwa warrior for perhaps as long as ten years, and distinguished himself with his courage, though he did not rise, as legend has it, to a great position. Dingiswayo had been exiled after a failed attempt to oust his father. There were a number of other groups in the region (including Mabhudu, Dlamini, Mkhize, Qwabe, and Ndwandwe). Along with them, Dingiswayo helped develop new ideas of military and social organisation, in particular the ibutho, sometimes translated as "regiment" or "troop". They were probably responding to slaving pressures from southern Mozambique.

The ibutho was rather an age-based labour gang (cohort) which included some better refined military activities, but by no means exclusively. Most battles before this time were to settle disputes, and while the appearance of ibutho lempi (fighting unit) dramatically changed warfare at times, it largely remained an instrument for seasonal raiding and political persuasion rather than outright slaughter.

Shaka granted permission to Europeans to enter Zulu territory on rare occasions. Henry Francis Fynn provided medical treatment to the king after an assassination attempt from a rival tribe member hidden in a crowd (see account of Nathaniel Isaacs). To show his gratitude, Shaka permitted European settlers to enter and operate in the Zulu kingdom. This would open the door for future British incursions into the Zulu kingdom that were not so peaceful. Shaka observed several demonstrations of European technology and knowledge, but held that the Zulu way was superior to that of the foreigners.

The successor of Senzangakona

On the death of Senzangakona, Dingiswayo aided Shaka to defeat his brother and assume leadership ca. 1816. Shaka began to further refine the ibutho system used by Dingiswayo and others and, with Mthethwa's support over the next several years, forged alliances with his smaller neighbours, to counter the growing threat from Ndwandwe raiding from the north. The initial Zulu manoeuvres were primarily defensive in nature, as Shaka preferred to intervene or apply pressure diplomatically, aided by occasional judicious assassinations. His changes to local society built on existing structures. Although he preferred social and propagandistic political methods, he also engaged in a number of battles, as the Zulu sources make clear.

When Dingiswayo was murdered by Zwide,

a powerful chief of the Ndwandwe (Nxumalo) clan, Shaka sought to avenge

his death. At some point Zwide barely escaped Shaka, though the exact

details are not known. In that encounter Zwide's mother Ntombazi, a

Sangoma

(Zulu seer or shaman), was killed by Shaka. Shaka chose a particularly

gruesome revenge on her, locking her in a house and placing jackals or

hyenas inside: they devoured her and, in the morning, Shaka burned the

house to the ground. Despite carrying out this revenge, Shaka continued

his pursuit of Zwide. It was not until around 1825 that the two great

military men would meet, near Phongola, in what would be their final

meeting. Phongola is near the present day border of KwaZulu-Natal,

a province in South Africa. Shaka was victorious in battle, although

his forces sustained heavy casualties, which included his head military

commander, Umgobhozi Ovela Entabeni.

In the initial years, Shaka had neither the influence nor reputation to compel any but the smallest of groups to join him, and he operated under Dingiswayo's aegis until the latter's death at the hands of Zwide's Ndwandwe. At this point, Shaka moved southwards across the Thukela River, establishing his capital Bulawayo in Qwabe territory; he never did move back into the traditional Zulu heartland. In Qwabe, Shaka may have intervened in an existing succession dispute to help his own choice, Nqetho, into power; Nqetho then ruled as a proxy chieftain for Shaka.

Shaka's hegemony was primarily based on military might, smashing rivals and incorporating scattered remnants into his own army. He supplemented this with a mixture of diplomacy and patronage, incorporating friendly chieftains, including Zihlandlo of the Mkhize, Jobe of the Sithole, and Mathubane of the Thuli. These peoples were never defeated in battle by the Zulu; they did not have to be. Shaka won them over by subtler tactics, such as patronage and reward. As for the ruling Qwabe, they began re-inventing their genealogies to give the impression that Qwabe and Zulu were closely related in the past. In this way a greater sense of cohesion was created, though it never became complete, as subsequent civil wars attest.

His half-brother, Sigujana, who had been destined to become Zulu Chief, was killed.

The coup was relatively bloodless and accepted by the Zulu. Shaka still recognised Dingiswayo and his larger Mthethwa clan as overlord after he returned to the Zulu but, some years later, Dingiswayo was ambushed by Zwide's amaNdwandwe and killed. There is no evidence to suggest that Shaka betrayed Dingiswayo. Indeed, the core Zulu had to retreat before several Ndwandwe incursions; the Ndwandwe was clearly the most aggressive grouping in the sub-region.

Shaka was able to form an alliance with the leaderless Mthethwa clan and was able to establish himself amongst the Qwabe, after Phakathwayo was overthrown with relative ease. With Qwabe, Hlubi and Mkhize support, Shaka was finally able to summon a force capable of resisting the Ndwandwe (of the Nxumalo clan). Historian Donald Morris states that Shaka's first major battle against Zwide, of the Ndwandwe, was the Battle of Gqokli Hill, on the Mfolozi river. Shaka's troops maintained a strong position on the crest of the hill. A frontal assault by their opponents failed to dislodge them and Shaka sealed the victory by sending his reserve forces in a sweep around the hill to attack the enemy's rear. Losses were high overall but the efficacy of the new Shakan innovations was proved. It is probable that, over time, the Zulu were able to hone and improve their encirclement tactics.

Another decisive fight eventually took place on the Mhlatuze river, at the confluence with the Mvuzane stream. In a two-day running battle, the Zulu inflicted a resounding defeat on their opponents. Shaka then led a fresh reserve some seventy miles to the royal kraal of Zwide, ruler of the Ndwandwe, and destroyed it. Zwide himself escaped with a handful of followers before falling foul of a chieftainess named Mjanji, ruler of the baPedi clan (he died in mysterious circumstances soon afterward). Shaka's general Soshangane (of the Shangaan) moved north towards what is now Mozambique to inflict further damage on less resistant foes and take advantage of slaving opportunities, obliging Portuguese traders to give tribute. Shaka later had to contend again with Zwide's son Sikhunyane in 1826.

According to Donald Morris in this mourning period Shaka ordered that no crops should be planted during the following year, no milk (the basis of the Zulu diet at the time) was to be used, and any woman who became pregnant was to be killed along with her husband. At least 7,000 people who were deemed to be insufficiently grief-stricken were executed, though it wasn't restricted to humans, cows were slaughtered so that their calves would know what losing a mother felt like.

The Zulu monarch was killed by three assassins sometime in 1828, September is the most often cited date, when almost all available Zulu manpower had been sent on yet another mass sweep to the north. This left the royal kraal critically short of security. It was all the conspirators needed—they being Shaka's half-brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana, and an iNduna called Mbopa. A diversion was created by Mbopa, and Dingane and Mhlangana struck the fatal blows. Shaka's corpse was dumped into an empty grain pit by his assassins and filled with stones and mud. The exact site is unknown. A monument was built at one alleged site. Historian Donald Morris holds that it is somewhere on Couper Street in the village of Stanger,South Africa.

Shaka's half-brother Dingane assumed power and embarked on an extensive purge of pro-Shaka elements and chieftains, running over several years, in order to secure his position. The initial problem Dingane faced was maintaining the loyalty of the Zulu fighting regiments or amabutho. He addressed this by allowing them to marry and set up a homestead (this was forbidden during Shaka's rule), and they also received cattle from Dingane. Loyalty was also maintained through fear as anyone who was suspected of rivaling Dingane was killed. He set up his main residence at Mmungungundlovo and established his authority over the Zulu kingdom. Dingane ruled for some twelve years, during which time he fought, disastrously, against the Voortrekkers, and against another half-brother Mpande, who, with Boer and British support, took over the Zulu leadership in 1840, and ruled for some 30 years. Later in the 19th century the Zulus would be one of the few African peoples who managed to defeat the British Army; at the Battle of Isandlwana.

Shaka is often said to have been dissatisfied with the long throwing "assegai," and credited with introducing a new variant of the weapon: the "iklwa," a short stabbing spear with a long, sword-like spearhead.

Though Shaka probably did not invent the iklwa, according to Zulu scholar John Laband (37), the leader did insist that his warriors train with the weapon, which gave them a "terrifying advantage over opponents who clung to the traditional practice of throwing their spears and avoiding hand-to-hand conflict." The throwing spear was not discarded but used as an initial missile weapon before close contact with the enemy, when the shorter stabbing spear was used in hand to hand combat.

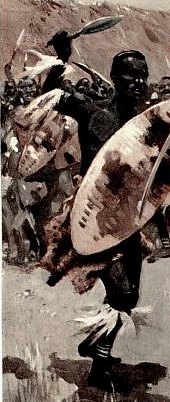

Shaka is also supposed to have introduced a larger, heavier shield made of cowhide and to have taught each warrior how to use the shield's left side to hook the enemy's shield to the right, exposing his ribs for a fatal spear stab. In Shaka's time, these cowhide shields were supplied by the king and remained his property (Laband 37). Different colored shields distinguished different amabutho within Shaka's army. Some had black shields, others used white shields with black spots, some had white shields with brown spots, while others used pure brown or white shields (37).

Historian John Laband dismisses these stories as myth. "What are we to make, then, of [European trader Henry Francis] Fynn's statement that once the Zulu army reached hard and stony ground in 1826, Shaka ordered sandals of ox-hide to be made for himself?"

The idea of a 50 miles (80 km) march in a single day is also dismissed as ridiculous. Laband further claims that even though these stories have been repeated by "astonished and admiring white commentators," the Zulu army covered "no more than 19 kilometres (12 mi) a day, and usually went only about 14 kilometres (8.7 mi).". Furthermore, Zulus under Shaka sometimes advanced more slowly. They spent two whole days recuperating in one instance, and on another they rested for a day and two nights before pursuing their enemy. Several other historians of the Zulu, and the Zulu military system however, affirm the mobility rate of up to 50 miles per day.

The expanding Zulu power inevitably clashed with European hegemony in

the decades after Shaka's death. In fact, European travellers to

Shaka's kingdom demonstrated advanced technology such as firearms and

writing, but the Zulu monarch was less than convinced. There was no need

to record messages, he held, since his messengers stood under penalty

of death should they bear inaccurate tidings. As for firearms, Shaka

acknowledged their utility as missile weapons after seeing

muzzle-loaders demonstrated, but argued that in the time a gunman took

to reload, he would be swamped by charging spear-wielding warriors.

The expanding Zulu power inevitably clashed with European hegemony in

the decades after Shaka's death. In fact, European travellers to

Shaka's kingdom demonstrated advanced technology such as firearms and

writing, but the Zulu monarch was less than convinced. There was no need

to record messages, he held, since his messengers stood under penalty

of death should they bear inaccurate tidings. As for firearms, Shaka

acknowledged their utility as missile weapons after seeing

muzzle-loaders demonstrated, but argued that in the time a gunman took

to reload, he would be swamped by charging spear-wielding warriors.

The first major clash after Shaka's death took place under his successor Dingane, against expanding European Voortrekkers from the Cape. Initial Zulu success rested on fast-moving surprise attacks and ambushes, but the Voortrekkers recovered and dealt the Zulu a severe defeat from their fortified wagon laager at the Battle of Blood River. The second major clash was against the British during 1879. Once again, most Zulu successes rested on their mobility, ability to screen their forces and to close when their opponents were unfavourably deployed. Their major victory at the Battle of Isandlwana is well known, but they also forced back a British column at the Battle of Hlobane mountain, by deploying fast-moving regiments over a wide area of rugged ravines and gullies, and attacking the British who were forced into a rapid disorderly fighting retreat, back to the town of Kambula.

Scholarship in recent years has revised views of the sources on

Shaka's reign. The earliest are two eyewitness accounts written by white

adventurer-traders who met Shaka during the last four years of his

reign. Nathaniel Isaacs published his Travels and Adventures in Eastern Africa

in 1836, creating a picture of Shaka as a degenerate and pathological

monster which survives in modified forms to this day. Isaacs was aided

in this by Henry Francis Fynn, whose diary (actually a rewritten collage

of various papers) was edited by James Stuart only in 1950.

Their accounts may be balanced by the rich resource of oral histories collected around 1900 by the same James Stuart, now published in 6 volumes as The James Stuart Archive. Stuart's early 20th century work was continued by D. McK. Malcolm in 1950. These and other sources such as A. T. Bryant gives us a more Zulu-centred picture. Most popular accounts are based on E. A. Ritter's novel Shaka Zulu (1955), a potboiling romance which was re-edited into something more closely resembling a history. The work of John Wright (history professor at University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg), Julian Cobbing and Dan Wylie (Rhodes University, Grahamstown) have been among a number of writers who have modified these stories.

Various modern historians writing on Shaka and the Zulu point to the uncertain nature of Fynn and Isaac's accounts of Shaka's reign. A standard general reference work in the field is Donald Morris's "The Washing of The Spears", which notes the sources, as a whole, for this historical era are not the best. Morris nevertheless references a large number of sources, including Stuart, and A. T. Bryant's extensive but uneven "Olden Times in Zululand and Natal", which is based on four decades of exhaustive interviews of tribal sources. After sifting through these sources and noting their strengths and weaknesses, Morris generally credits Shaka with a large number of military and social innovations, and this is the general consensus in the field.

A 1998 study by historian Carolyn Hamilton summarizes much of the scholarship on Shaka towards the dawn of the 21st century in areas ranging from ideology, politics and culture, to the use of his name and image in a popular South African theme park, Shakaland. It argues that in many ways, the image of Shaka has been "invented" in the modern era according to whatever agenda persons hold. This "imagining of Shaka" it is held, should be balanced by a sober view of the historical record, and allow greater scope for the contributions of indigenous African discourse.

Military historians of the Zulu War must also be considered for their description of Zulu fighting methods and tactics, including authors like Ian Knight and Robert Edgerton. General histories of Southern Africa are also valuable including Noel Mostert's "Frontiers" and a detailed account of the results from the Zulu expansion, J. D. Omer-Cooper's "The Zulu Aftermath", which advances the traditional Mfecane theory.

At the time of his death, Shaka ruled over 250,000 people and could muster more than 50,000 warriors. His 10-year-long kingship resulted in a massive number of deaths, mostly due to the disruptions the Zulu caused in neighbouring tribes, although the exact death toll is a matter of scholarly dispute. Further unquantifiable deaths occurred during mass tribal migrations to escape his armies.

Among the many fascinating cases of the Mfecane is that of Mzilikazi of the Khumalo who was a 'general' of Shaka's, who fled Shaka's employ, and in turn conquered an empire in Zimbabwe, after clashing with European groups like the Boers. The settling of Mzilikazi's people, the AmaNdebele or Matabele, in the south of Zimbabwe with the concomitant driving of the AmaShona into the north caused a tribal conflict which still resonates today. Other notable figures to arise from the Mfecane include Shoshangane, who expanded from the Zulu area into what is now Mozambique. Shaka was clearly a tough, able leader, the most able of his time who, during the last four years of his reign, indulged in several long-distance raids.

William Rubinstein wrote that "Western guilt over colonialism, have also accounted for much of this distortion of what pre-literate societies actually were like, as does the wish to avoid anything which smacks of racism, even when this means distorting the actual and often appalling facts of life in many pre-literate societies". Rubinstein also notes:

Wylie also argues that the view of Shaka as a monster who started the Mfecane does not hold up under hard analysis, and that regional upheavals and other factors were already in play in the environment when Shaka appeared.

Shaka's enemies described him as ugly in some respects. He had a big nose, according to Baleka of the Qwabe, as told by her father. He also had two prominent front teeth. Her father also told Baleka that Shaka spoke as though "his tongue were too big for his mouth." Many said that he talked with a speech impediment.

There is an anecdote that Shaka joked with one of his friends, Magaye, that he could not kill Magaye because he would be laughed at. Supposedly if he killed Magaye, it would appear to be out of jealousy because Magaye was so handsome and "Shaka himself was ugly, with a protruding forehead".

The figure of Shaka still sparks interest among not only the

contemporary Zulu but many worldwide who have encountered the tribe and

its history. The current tendency appears to be to lionise him; popular

film and other media have certainly contributed to his appeal. Against

this must be balanced the devastation and destruction that he wrought.

Certain aspects of traditional Zulu culture still revere the dead

monarch, as the typical praise song below attests. It should be noted

that the praise song is one of the most widely used poetic forms in

Africa, applying not only to gods but to men, animals, plants and even

towns.

Other Zulu sources are sometimes critical of Shaka, and numerous negative images abound in Zulu oral history. When Shaka's mother Nandi died for example, the monarch ordered a massive outpouring of grief including mass executions, forbidding the planting of crops or the use of milk, and the killing of all pregnant women and their husbands. Oral sources record that in this period of devastation, a singular Zulu, a man named Gala, eventually stood up to Shaka and objected to these measures, pointing out that Nandi was not the first person to die in Zululand. Taken aback by such candid talk, the Zulu king is supposed to have called off the destructive edicts, rewarding the blunt teller-of-truths with a gift of cattle.

The figure of Shaka thus remains an ambiguous one in African oral tradition, defying simplistic depictions of the Zulu king as a heroic, protean nation builder on one hand, or a depraved monster on the other. This ambiguity continues to lend the image of Shaka its continued power and influence, almost two centuries after his death.

In the initial years, Shaka had neither the influence nor reputation to compel any but the smallest of groups to join him, and he operated under Dingiswayo's aegis until the latter's death at the hands of Zwide's Ndwandwe. At this point, Shaka moved southwards across the Thukela River, establishing his capital Bulawayo in Qwabe territory; he never did move back into the traditional Zulu heartland. In Qwabe, Shaka may have intervened in an existing succession dispute to help his own choice, Nqetho, into power; Nqetho then ruled as a proxy chieftain for Shaka.

Expansion of power and conflict with Zwide

As Shaka became more respected by his people, he was able to spread his ideas with greater ease. Because of his background as a soldier, Shaka taught the Zulus that the most effective way of becoming powerful quickly was by conquering and controlling other tribes. His teachings greatly influenced the social outlook of the Zulu people. The Zulu tribe soon developed a "warrior" mindset, which Shaka turned to his advantage.Shaka's hegemony was primarily based on military might, smashing rivals and incorporating scattered remnants into his own army. He supplemented this with a mixture of diplomacy and patronage, incorporating friendly chieftains, including Zihlandlo of the Mkhize, Jobe of the Sithole, and Mathubane of the Thuli. These peoples were never defeated in battle by the Zulu; they did not have to be. Shaka won them over by subtler tactics, such as patronage and reward. As for the ruling Qwabe, they began re-inventing their genealogies to give the impression that Qwabe and Zulu were closely related in the past. In this way a greater sense of cohesion was created, though it never became complete, as subsequent civil wars attest.

His half-brother, Sigujana, who had been destined to become Zulu Chief, was killed.

The coup was relatively bloodless and accepted by the Zulu. Shaka still recognised Dingiswayo and his larger Mthethwa clan as overlord after he returned to the Zulu but, some years later, Dingiswayo was ambushed by Zwide's amaNdwandwe and killed. There is no evidence to suggest that Shaka betrayed Dingiswayo. Indeed, the core Zulu had to retreat before several Ndwandwe incursions; the Ndwandwe was clearly the most aggressive grouping in the sub-region.

Shaka was able to form an alliance with the leaderless Mthethwa clan and was able to establish himself amongst the Qwabe, after Phakathwayo was overthrown with relative ease. With Qwabe, Hlubi and Mkhize support, Shaka was finally able to summon a force capable of resisting the Ndwandwe (of the Nxumalo clan). Historian Donald Morris states that Shaka's first major battle against Zwide, of the Ndwandwe, was the Battle of Gqokli Hill, on the Mfolozi river. Shaka's troops maintained a strong position on the crest of the hill. A frontal assault by their opponents failed to dislodge them and Shaka sealed the victory by sending his reserve forces in a sweep around the hill to attack the enemy's rear. Losses were high overall but the efficacy of the new Shakan innovations was proved. It is probable that, over time, the Zulu were able to hone and improve their encirclement tactics.

Another decisive fight eventually took place on the Mhlatuze river, at the confluence with the Mvuzane stream. In a two-day running battle, the Zulu inflicted a resounding defeat on their opponents. Shaka then led a fresh reserve some seventy miles to the royal kraal of Zwide, ruler of the Ndwandwe, and destroyed it. Zwide himself escaped with a handful of followers before falling foul of a chieftainess named Mjanji, ruler of the baPedi clan (he died in mysterious circumstances soon afterward). Shaka's general Soshangane (of the Shangaan) moved north towards what is now Mozambique to inflict further damage on less resistant foes and take advantage of slaving opportunities, obliging Portuguese traders to give tribute. Shaka later had to contend again with Zwide's son Sikhunyane in 1826.

Death and succession

Dingane and Mhlangana, Shaka's half-brothers, appear to have made at least two attempts to assassinate Shaka before they succeeded, with perhaps support from Mpondo elements, and some disaffected iziYendane people. While the British colonialists considered his regime to be a future threat, allegations that white traders wished his death are problematic given that Shaka had granted concessions to whites prior to his death, including the right to settle at Port Natal (now Durban). Shaka had made enough enemies among his own people to hasten his demise. It came relatively quickly after the devastation caused by Shaka's erratic behavior after the death of his mother Nandi.According to Donald Morris in this mourning period Shaka ordered that no crops should be planted during the following year, no milk (the basis of the Zulu diet at the time) was to be used, and any woman who became pregnant was to be killed along with her husband. At least 7,000 people who were deemed to be insufficiently grief-stricken were executed, though it wasn't restricted to humans, cows were slaughtered so that their calves would know what losing a mother felt like.

The Zulu monarch was killed by three assassins sometime in 1828, September is the most often cited date, when almost all available Zulu manpower had been sent on yet another mass sweep to the north. This left the royal kraal critically short of security. It was all the conspirators needed—they being Shaka's half-brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana, and an iNduna called Mbopa. A diversion was created by Mbopa, and Dingane and Mhlangana struck the fatal blows. Shaka's corpse was dumped into an empty grain pit by his assassins and filled with stones and mud. The exact site is unknown. A monument was built at one alleged site. Historian Donald Morris holds that it is somewhere on Couper Street in the village of Stanger,South Africa.

Shaka's half-brother Dingane assumed power and embarked on an extensive purge of pro-Shaka elements and chieftains, running over several years, in order to secure his position. The initial problem Dingane faced was maintaining the loyalty of the Zulu fighting regiments or amabutho. He addressed this by allowing them to marry and set up a homestead (this was forbidden during Shaka's rule), and they also received cattle from Dingane. Loyalty was also maintained through fear as anyone who was suspected of rivaling Dingane was killed. He set up his main residence at Mmungungundlovo and established his authority over the Zulu kingdom. Dingane ruled for some twelve years, during which time he fought, disastrously, against the Voortrekkers, and against another half-brother Mpande, who, with Boer and British support, took over the Zulu leadership in 1840, and ruled for some 30 years. Later in the 19th century the Zulus would be one of the few African peoples who managed to defeat the British Army; at the Battle of Isandlwana.

Shaka's social and military revolution

Weapons changesShaka is often said to have been dissatisfied with the long throwing "assegai," and credited with introducing a new variant of the weapon: the "iklwa," a short stabbing spear with a long, sword-like spearhead.

Though Shaka probably did not invent the iklwa, according to Zulu scholar John Laband (37), the leader did insist that his warriors train with the weapon, which gave them a "terrifying advantage over opponents who clung to the traditional practice of throwing their spears and avoiding hand-to-hand conflict." The throwing spear was not discarded but used as an initial missile weapon before close contact with the enemy, when the shorter stabbing spear was used in hand to hand combat.

Shaka is also supposed to have introduced a larger, heavier shield made of cowhide and to have taught each warrior how to use the shield's left side to hook the enemy's shield to the right, exposing his ribs for a fatal spear stab. In Shaka's time, these cowhide shields were supplied by the king and remained his property (Laband 37). Different colored shields distinguished different amabutho within Shaka's army. Some had black shields, others used white shields with black spots, some had white shields with brown spots, while others used pure brown or white shields (37).

Mobility of the army

The story that sandals were discarded to toughen the feet of Zulu warriors has been noted in various military accounts such as "The Washing of the Spears," "Like Lions They Fought" and "Anatomy of the Zulu Army." Implementation was typically blunt. Those who objected to going without sandals were simply killed. Shaka drilled his troops frequently, forced marches sometimes covering more than 50 miles (80 km) a day in a fast trot over hot, rocky terrain. He also drilled the troops to carry out encirclement tactics.Historian John Laband dismisses these stories as myth. "What are we to make, then, of [European trader Henry Francis] Fynn's statement that once the Zulu army reached hard and stony ground in 1826, Shaka ordered sandals of ox-hide to be made for himself?"

The idea of a 50 miles (80 km) march in a single day is also dismissed as ridiculous. Laband further claims that even though these stories have been repeated by "astonished and admiring white commentators," the Zulu army covered "no more than 19 kilometres (12 mi) a day, and usually went only about 14 kilometres (8.7 mi).". Furthermore, Zulus under Shaka sometimes advanced more slowly. They spent two whole days recuperating in one instance, and on another they rested for a day and two nights before pursuing their enemy. Several other historians of the Zulu, and the Zulu military system however, affirm the mobility rate of up to 50 miles per day.

Well-organised logistic support by youth formations

Young boys aged six and over joined Shaka's force as apprentice warriors (udibi) and served as carriers of rations, supplies like cooking pots and sleeping mats, and extra weapons until they joined the main ranks. It is sometimes held that such support was used more for very light forces designed to extract tribute in cattle, women or young men from neighbouring groups. Nevertheless, the concept of "light" forces is questionable. The fast-moving Zulu raiding party or "ibutho lempi" on a mission invariably traveled light, driving cattle as provisions on the hoof, and were not weighed down with heavy weapons and supply packs. The herdboy logistic structure was deployed in support of these relatively short-term operations, and was easily adaptable to large or small expeditions.The age-grade regimental system

Age-grade groupings of various sorts were common in the Bantu culture of the day, and indeed are still important in much of Africa. Age grades were responsible for a variety of activities, from guarding the camp, to cattle herding, to certain rituals and ceremonies. Shaka organised various grades into regiments, and quartered them in special military kraals, with regiments having their own distinctive names and insignia. The regimental system clearly built on existing tribal cultural elements that could be adapted and shaped to fit an expansionist agenda. There was no need to look for European inspiration hundreds of miles away.The "bull horn" formation

Most historians credit Shaka with initial development of the famous "bull horn" formation. It was composed of three elements:- The main force, the "chest," closed with the enemy Impi and pinned it in position. The warriors who comprised the "chest" were senior veterans.

- The "horns," while the enemy Impi was pinned by the "chest," would flank the Impi from both sides and encircle it; in conjunction with the "chest" they would then destroy the trapped force. The warriors who comprised the "horns" were young and fast juniors.

- The "loins," a large reserve, was placed, seated, behind the "chest" with their backs to the battle. The "loins" would be committed wherever the enemy Impi threaten to break out of the encirclement.

Organization and leadership of the Zulu forces

The host were generally partitioned into three levels: regiments, corps of several regiments, and "armies" or bigger formations, although the Zulu did not use these terms in the modern sense. Any grouping of men on a mission could collectively be called an impi, whether a raiding party of 100 or horde of 10,000. Numbers were not uniform, but dependent on a variety of factors including assignments by the king or the manpower mustered by various clan chiefs or localities. A regiment might be 400 or 4000 men. These were grouped into corps that took their name from the military kraals where they were mustered, or sometimes the dominant regiment of that locality.Shakan methods versus European technology

Shaka dismissed firearms

as ineffective against the quick encirclements of charging spearmen.

Although ultimately failing against modern rifle and artillery fire in

1879, his theory achieved some success at Isandlwana.

The first major clash after Shaka's death took place under his successor Dingane, against expanding European Voortrekkers from the Cape. Initial Zulu success rested on fast-moving surprise attacks and ambushes, but the Voortrekkers recovered and dealt the Zulu a severe defeat from their fortified wagon laager at the Battle of Blood River. The second major clash was against the British during 1879. Once again, most Zulu successes rested on their mobility, ability to screen their forces and to close when their opponents were unfavourably deployed. Their major victory at the Battle of Isandlwana is well known, but they also forced back a British column at the Battle of Hlobane mountain, by deploying fast-moving regiments over a wide area of rugged ravines and gullies, and attacking the British who were forced into a rapid disorderly fighting retreat, back to the town of Kambula.

Shaka as the creator of a revolutionary warfare style

A number of historians argue that Shaka 'changed the nature of warfare in Southern Africa' from 'a ritualised exchange of taunts with minimal loss of life into a true method of subjugation by wholesale slaughter'. Others dispute this characterization (see Scholarship section below). A number of writers focus on Shaka's military innovations such as the iklwa – the Zulu thrusting spear, and the "buffalo horns" formation. This combination has been compared to the standardization implemented by the reorganised Roman legions under Marius.- Combined with Shaka's "buffalo horns" attack formation for surrounding and annihilating enemy forces, the Zulu combination of iklwa and shield—similar to the Roman legionaries' use of gladius and scutum—was devastating. By the time of Shaka's assassination in 1828, it had made the Zulu kingdom the greatest power in southern Africa and a force to be reckoned with, even against Britain's modern army in 1879.

- Fanciful commentators called him Shaka, the Black Napoleon, and allowing for different societies and customs, the comparison is apt. Shaka is without doubt the greatest commander to come out of Africa.

Scholarship on Shaka

Their accounts may be balanced by the rich resource of oral histories collected around 1900 by the same James Stuart, now published in 6 volumes as The James Stuart Archive. Stuart's early 20th century work was continued by D. McK. Malcolm in 1950. These and other sources such as A. T. Bryant gives us a more Zulu-centred picture. Most popular accounts are based on E. A. Ritter's novel Shaka Zulu (1955), a potboiling romance which was re-edited into something more closely resembling a history. The work of John Wright (history professor at University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg), Julian Cobbing and Dan Wylie (Rhodes University, Grahamstown) have been among a number of writers who have modified these stories.

Various modern historians writing on Shaka and the Zulu point to the uncertain nature of Fynn and Isaac's accounts of Shaka's reign. A standard general reference work in the field is Donald Morris's "The Washing of The Spears", which notes the sources, as a whole, for this historical era are not the best. Morris nevertheless references a large number of sources, including Stuart, and A. T. Bryant's extensive but uneven "Olden Times in Zululand and Natal", which is based on four decades of exhaustive interviews of tribal sources. After sifting through these sources and noting their strengths and weaknesses, Morris generally credits Shaka with a large number of military and social innovations, and this is the general consensus in the field.

A 1998 study by historian Carolyn Hamilton summarizes much of the scholarship on Shaka towards the dawn of the 21st century in areas ranging from ideology, politics and culture, to the use of his name and image in a popular South African theme park, Shakaland. It argues that in many ways, the image of Shaka has been "invented" in the modern era according to whatever agenda persons hold. This "imagining of Shaka" it is held, should be balanced by a sober view of the historical record, and allow greater scope for the contributions of indigenous African discourse.

Military historians of the Zulu War must also be considered for their description of Zulu fighting methods and tactics, including authors like Ian Knight and Robert Edgerton. General histories of Southern Africa are also valuable including Noel Mostert's "Frontiers" and a detailed account of the results from the Zulu expansion, J. D. Omer-Cooper's "The Zulu Aftermath", which advances the traditional Mfecane theory.

History and legacy

The increased military efficiency led to more and more clans being incorporated into Shaka's Zulu empire, while other tribes moved away to be out of range of Shaka's impis. The ripple effect caused by these mass migrations would become known (though only in the twentieth century) as the Mfecane (annihilation). Some groups which moved off (like the Hlubi and Ngwane to the north of the Zulus) could have been impelled by the Ndwandwe, not the Zulu. Some moved south (like the Chunu and the Thembe), but never suffered much in the way of attack; it was precautionary, and they left many people behind in their traditional homelands.At the time of his death, Shaka ruled over 250,000 people and could muster more than 50,000 warriors. His 10-year-long kingship resulted in a massive number of deaths, mostly due to the disruptions the Zulu caused in neighbouring tribes, although the exact death toll is a matter of scholarly dispute. Further unquantifiable deaths occurred during mass tribal migrations to escape his armies.

Among the many fascinating cases of the Mfecane is that of Mzilikazi of the Khumalo who was a 'general' of Shaka's, who fled Shaka's employ, and in turn conquered an empire in Zimbabwe, after clashing with European groups like the Boers. The settling of Mzilikazi's people, the AmaNdebele or Matabele, in the south of Zimbabwe with the concomitant driving of the AmaShona into the north caused a tribal conflict which still resonates today. Other notable figures to arise from the Mfecane include Shoshangane, who expanded from the Zulu area into what is now Mozambique. Shaka was clearly a tough, able leader, the most able of his time who, during the last four years of his reign, indulged in several long-distance raids.

Disruptions of the Mfecane

The theory of the Mfecane holds that the aggressive expansion of Shaka's armies caused a brutal chain reaction across the southern areas of the continent, as dispossessed tribe after tribe turned on their neighbours in a deadly cycle of fight and conquest. This theory must be treated with caution, some scholars hold, as it generally neglects several other factors such as the impact of white encroachment, slave trading and expansion in that area of Southern Africa around the same time. The development of the view that Shaka was the monster responsible for the devastation is based on the need of apartheid era historians to justify the apartheid regime's racist policies. Other scholars acknowledge distortion of the historical record by apartheid supporters and shady white traders seeking to cover their tracks, but dispute the revisionist approach, noting that stories of cannibalism, raiding, burning of villages, or mass slaughter were not developed out of thin air but based on the clearly documented accounts of hundreds of black victims, and refugees. Confirmation of such accounts can also be seen in modern archaeology of the village of Lepalong, an entire settlement built underground to shelter remmnants of the Kwena people from 1827–36 against the tide of disruption that engulfed the region during Shakan times.William Rubinstein wrote that "Western guilt over colonialism, have also accounted for much of this distortion of what pre-literate societies actually were like, as does the wish to avoid anything which smacks of racism, even when this means distorting the actual and often appalling facts of life in many pre-literate societies". Rubinstein also notes:

"One element in Shaka's destruction was to create a vast artificial desert around his domain ... 'to make the destruction complete, organized bands of Zulu murderers regularly patrolled the waste, hunting for any stray men and running them down like wild pig.' ... An area 200 miles to the north of the center of the state, 300 miles to the west, and 500 miles to the south was ravaged and depopulated ..."Other writers such as Dan Wylie (2011) express skepticism of the portrayal of Shaka as a pathological monster destroying everything within reach. They note that attempts to distort his life and image have been systematic- beginning with the first white visitors to his kingdom. One (Nathaniel Isaccs) wrote to Fynn:

- Here you are about to publish. Do make Shaka out to be as bloodthristy as you can; it helps swell out the work and make it interesting.

- [Fynn] stated that Shaka had killed 'a million people.' You will still find this figure, and higher, repeated in today's literature. However, Fynn had no way of knowing any such thing: it was a thumb-suck based in a particular view of Shaka - Shaka as a kind of genocidal maniac, an unresting killing-machine. But why the inventive lie? ... Fynn was bidding for a stretch of land, which allegedly had been depopulated by Shaka... (he insinuated), Shaka didn't deserve that land anyway because he was such a brute, while he - Fynn - was a lonely, morally upright pioneer of civilisation.

Wylie also argues that the view of Shaka as a monster who started the Mfecane does not hold up under hard analysis, and that regional upheavals and other factors were already in play in the environment when Shaka appeared.

- "In short, the geographic isolationism of the mainstream 'mfecane' model doesn't hold. Secondly, the 'mfecane' cannot be isolated in time. Major changes were happening over a longer period than just on the 1810s.. a third reason why the 'mfecane' model doesn't hold is that political developments in response to the violence were not centered on Shaka's Zulu. Around 1750, it is now clear, slaving, trade, violence, the use of defensive hilltop settlement, and more centralised and militaeised groupings were developing. all much the same time, right across the region."

Physical descriptions

Though much remains unknown about Shaka's personal appearance, sources tend to agree he had a strong, muscular body and was not fat. He was of medium height and his skin tone was dark brown. He was uncircumcised, which bucked a trend in Zulu culture near that time.Shaka's enemies described him as ugly in some respects. He had a big nose, according to Baleka of the Qwabe, as told by her father. He also had two prominent front teeth. Her father also told Baleka that Shaka spoke as though "his tongue were too big for his mouth." Many said that he talked with a speech impediment.

There is an anecdote that Shaka joked with one of his friends, Magaye, that he could not kill Magaye because he would be laughed at. Supposedly if he killed Magaye, it would appear to be out of jealousy because Magaye was so handsome and "Shaka himself was ugly, with a protruding forehead".

Shaka in Zulu culture

Other Zulu sources are sometimes critical of Shaka, and numerous negative images abound in Zulu oral history. When Shaka's mother Nandi died for example, the monarch ordered a massive outpouring of grief including mass executions, forbidding the planting of crops or the use of milk, and the killing of all pregnant women and their husbands. Oral sources record that in this period of devastation, a singular Zulu, a man named Gala, eventually stood up to Shaka and objected to these measures, pointing out that Nandi was not the first person to die in Zululand. Taken aback by such candid talk, the Zulu king is supposed to have called off the destructive edicts, rewarding the blunt teller-of-truths with a gift of cattle.

The figure of Shaka thus remains an ambiguous one in African oral tradition, defying simplistic depictions of the Zulu king as a heroic, protean nation builder on one hand, or a depraved monster on the other. This ambiguity continues to lend the image of Shaka its continued power and influence, almost two centuries after his death.

Legacy

- The King Shaka International Airport at La Mercy, 35 km north of the Durban city centre was opened on 1 May 2010 in preparation for the 2010 FIFA World Cup after a protracted debate over the name lasting over two years.

- uShaka Marine World, an aquatic theme park in Durban opened in 2004.